Forewords

We need the Food Equity Roundtable to bring together all the different forces working to distribute food both through the regular channels and to LA County’s exceptionally large food insecure populations. The Food Equity Roundtable is in fact an overdue creation.

Frank Tamborello

Executive Director, Hunger Action Los Angeles

1. LA County

Food Equity Roundtable

Hunger peaked at a record high during the pandemic, with 34% of all LA County households reporting food insecurity. People of color shouldered the burden of hunger at disproportionately high rates, illuminating how structural racism has produced a fragile and insufficient food system. Motivated by this incredible hardship, the County of Los Angeles and LA-based foundations, who have long partnered in support of food and nutrition security, mobilized to disburse resources and provide leadership through an unprecedented private-public partnership. This new partnership will address food system inequities that existed long before the pandemic and that persist to this day. This plan will play a key role towards supporting the White House goal of ending hunger and diet-related disease by 2030.

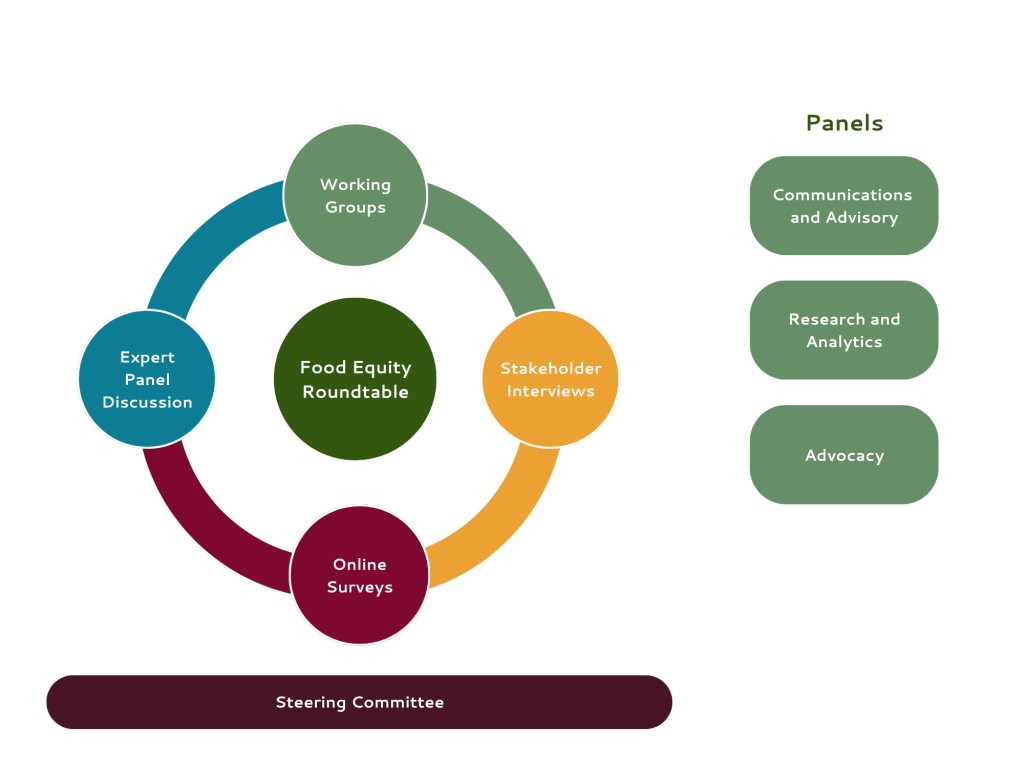

In February 2021, the LA County Chief Sustainability Office, Annenberg Foundation, California Community Foundation, and Weingart Foundation came together to support a motion to pilot the Los Angeles Food Equity Roundtable- a committee of 20 cross-sector leaders dedicated to achieving equity in food systems across LA County.

Co-Chaired by Cinny Kennard, Executive Director of the Annenberg Foundation, and Ali Frazzini, Sustainability Policy Advisor for the LA County Chief Sustainability Office, the Roundtable is committed to ending food and nutrition insecurity in LA County by:

- Improving the affordability of healthy foods

- Increasing equitable access to healthy foods

- Building market demand and consumption of healthy food

- Supporting sustainability and resilience in the food supply

In addition to the Roundtable members, over 200 thought partners dedicated to social justice and food equity participated in working groups and listening tours, which informed the objectives, strategies, and actions outlined in this plan. We will work with our cross-sector partners representing government agencies, community-based organizations, academia, the private sector, and other local and national thought leaders to achieve our common mission. Though food insecurity was a crisis long before the pandemic, together, we can end it.

We need shared data systems to get food to the people who need it.

The Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE) Nutrition and Wellness Unit is committed to providing technical assistance and professional learning opportunities for LEAs and schools using a comprehensive and integrated systems Whole-Child approach to improve food and nutrition security efforts among K-12 grade students and their families in Los Angeles County.

Maryam Shayegh

Nutrition and Wellness Coordinator, Los Angeles County Office of Education

A closer look:

By Gender

No Data Found

By Age

No Data Found

By Race

No Data Found

2. Food and Nutrition

Security in LA County

1/10

Angelenos impacted by food insecurity pre-pandemic.

4/10

Latino and/or Black households reported food insecurity in 2020.

1/4

Low-income households in LA remained food insecure in 2021.

The USDA defines food insecurity by a lack of consistent access to sufficient food. LA County was in a food insecurity crisis long before the pandemic, with 1 in 10 Angelenos impacted — nearly 1 million people. Due to systemic biases and injustices, some populations are much more vulnerable than others, which became especially clear during the COVID-19 pandemic; in 2020, approximately 4 out of every 10 Latino and/or Black households reported food insecurity — almost twice the proportion of white households.

Although food insecurity has improved since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 1 in 4 low-income households in Los Angeles County remained food insecure in 2021 — and racial inequities persist. The inequities reflect a long history of discrimination — policies and practices that segregated people by race and class throughout the County — which drained economic activity, including food production and retail, from communities of color. Neighborhoods in the Antelope Valley, East LA, and South LA Service Planning Areas of the County lack sufficient grocery stores and food assistance programs. As we work to recover and build more resilient communities and food systems post-pandemic, countywide food and nutrition security should be a social justice and public health goal.

Shocks to community food systems, like the COVID-19 pandemic, bring issues of food justice and food inequities to the forefront. The negative economic and health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have disproportionately affected low-income and marginalized groups, who were more likely to lose income or become ill. Both of these outcomes increased their risk of food and nutrition insecurity, equitable access to healthy, safe, and affordable food. Altogether, crises like the pandemic often exacerbate food, nutrition, and health inequities.

you

know?

Did you know?

There are over 224 distinct languages spoken in LA County , adding to the richness of our diversity and elevating the importance of culture and identity in all that we do.

“Language Spoken at Home

Los Angeles County.” Los Angeles Almanac.

© 1998-2019 Given Place Media, publishing as Los Angeles Almanac.

7 Nov. 2022 <http://www.laalmanac.com/population/po47.php>.

Improving access to healthy food can help reduce or avoid diet-related chronic diseases, including common conditions such as obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure. A roadmap to strengthening access to affordable and nourishing food and to help Los Angeles County transform its food infrastructure into a mission-driven, efficient food system that can support the local economy and invest in the public’s health is a giant step forward to advancing food and health equity for all.

Dr. Tony Kuo

Director, Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention,

Los Angeles County Department of Public Health

Our Vision:

A stronger and healthier LA County where communities have sufficient, nutritious, culturally appropriate food supplied by a resilient and sustainable food system.

Our Mission:

Implement cross-sector solutions to achieve food and nutrition security with a focus on under-resourced communities.

Our North Star Goal:

In the first phase of the strategic plan, we focused on gathering data and measuring the impact of current initiatives and policies that improve food and nutrition security among the target priority populations. As we continue to expand our efforts we will now adopt a more active role in developing and supporting pilot initiatives that directly address factors leading to food and nutrition insecurity. Going forward we will seek to expand our measures to include the social determinants of health.

RESULT:

- A healthier and more resilient Los Angeles County achieved through improved food and nutrition security among the most vulnerable populations

INDICATORS:

- Eliminating the gap in food security between the priority populations and LA County’s average

NATIONAL STRATEGY NORTH STAR GOAL:

Place your cursor on the clock to see the countdown to the national deadline to end hunger.

Goal 1

Goal 2

Goal 3

Goal 4

* These four goals are not meant to encompass all that needs to be done to achieve food equity; rather, they are defined ideals that complement each other as we begin to identify actions that can be taken.

We will achieve these goals through objectives, broad visions that account for the complexity and intersectionality of each equity goal with clear and discrete strategies accompanied by actions. Click on each objective to learn more.

STRATEGY 1.1: Support the growth of healthy food by promoting local farmers and urban agriculture alongside the consistent innovation of growing practices to meet evolving demands

STRATEGY 1.2: Increase efficiencies in food waste management and edible food recovery

STRATEGY 1.3: Adopt innovative approaches to addressing mobility barriers for end consumers with a focus on divested neighborhoods

STRATEGY 1.4: Make the food system more inclusive of small and minority-owned food suppliers and retailers

STRATEGY 1.5: Build resilience by shortening and diversifying supply chains and promoting climate-friendly food

STRATEGY 2.1: Connect and leverage multiple data sources to build a comprehensive shared understanding of the local food system

STRATEGY 2.2: Identify and address bias in food system data

STRATEGY 2.3: Invest in data and technology solutions to connect food supply chain partners to drive further efficiency in food waste and recovery management

STRATEGY 2.4: Streamline access to and improve navigation of nutrition programs, food resources, and services

STRATEGY 3.1: Adopt a human-centered approach to public benefit enrollment, program design, promotion, and case management

STRATEGY 3.2: Create a no-wrong-door system to streamline public benefit enrollment at any stage

STRATEGY 3.3: Target and maximize enrollment strategies that reduce stigma, especially for under-enrolled populations

STRATEGY 4.1: Promote and prescribe sufficient, safe, nutrient dense foods as a health and wellness strategy

STRATEGY 4.2: Adopt medically tailored meals as a meal option offered to meet dietary preferences and medical requirements

STRATEGY 5.1: Monitor and support food and nutrition security among priority populations

STRATEGY 5.2: Launch a comprehensive and sustained nutrition education campaign to reach priority populations

STRATEGY 5.3: Coordinate food and nutrition security efforts on LA County college campuses

STRATEGY 6.1: Enhance and expand quality after-school care programs and daycare centers

STRATEGY 6.2: Fortify collaboration across all sectors that support safety net programs, ensuring that each person is receiving all the benefits they are eligible for

STRATEGY 6.3: Strengthen the workforce development and employment opportunities in private, public, and nonprofit, sector food system jobs and industries

We are committed to data-driven evaluation and planning. In the first phase of implementation, we will focus our evaluation efforts on initiatives and policies aimed at directly improving food and nutrition security. As we continue to refine and expand our efforts, we will develop additional methods for addressing and monitoring the causal factors leading to food and nutrition insecurity.

4. Equity in the Food System

Food is a fundamental right protected under the international human rights and humanitarian law indicated under the United Nations Universal Declaration on Human Rights (Article 25) and the UN General Assembly International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (Article 11).

In the United States, various circumstances have denied people the basic right to food including many forms of discrimination: structural racism, ageism, and overall inequity. In fact, the ability to access healthy food varies by race, gender, ethnicity, age, education, income, neighborhood, immigrant status, physical disability, and more.

The LA County Food Equity Roundtable believes that personal characteristics should not affect access to healthy and nutritious food leading to healthy life outcomes. Our goals and objectives all center on ensuring equity and justice in the system. This means the plan is written with the understanding that everyone has unique challenges and struggles which should be met with unique supports that acknowledge the system is flawed.

Equity is one interpretation of fairness or justice. “Equity” means people should be treated uniquely by public policy to compensate for different circumstances and the consequent need for help from the government. Equity is commonly associated with equality in outcomes. The Food Equity Roundtable’s aims for:

Procedural Equity

People have agency over the types of food they produce, access, and/or consume

Distributional Equity

Different communities have equivalent levels of access to food

Structural Equity

Investments are made into the communities that have seen historical divestment

Transgenerational Equity

The food system is structured in a way that is sustainable for future generations

5. People at High-Risk for Food & Nutrition Insecurity

In working towards an LA County where all residents have just and equitable access to nutritious food, the first step is identifying populations that have disproportionately suffered from poor access to nutritious food.

Poverty is the number one cause of food insecurity; 35.3 percent of households with incomes below the U.S. Federal Poverty Line reported food insecurity in 2020. It contributes to high food insecurity rates among People of Color, who are more likely to live in poverty.

At the center of this plan is people. It’s the single parent who perseveres without affordable childcare; it’s the full-time college student with a full-time job, afraid to ask for help for fear of endangering their undocumented aunt; it’s the foster child that has just turned 18 and doesn’t have anyone to turn to; it’s an indigenous person lost in a data count and left behind. It’s the person that is all of these things at once, an intersectionality that makes navigating these challenges that much more difficult.

In working towards equitable access to nutritious food in LA County, we have identified priority populations that are highly vulnerable:

- 20.1% of children are food insecure nationally as per Feeding America 2020 research.

- In LA County, 1 in 4 children are food insecure.

Food insufficiency was more common among LGBT than non-LGBT people (12.7% vs. 7.8%) in the period between July 21 to October 11, 2021.

*Los Angeles FI regional level data not available for the segment

* Los Angeles FI regional level data not available for the segment

Up to 53% of US households with dietary restrictions reported to be food insecure prior to the pandemic.

*Limited empirical data for this population

As per USDA, an estimated 38% of households with very low food security included an adult with a disability

*Los Angeles FI regional level data not available for the segment

20% food insufficient compared with 16% in households with more than one parent, Apr 2020-Feb 2021 (Household Pulse Survey, Census Bureau)

As per CHIS 2020 data, food insecurity for LA County, households < 100% FPL was at 42%

About 50% increased risk for <100% FPL vs. about 20% increased risk for <300% FPL (vs. high income) (USC Public Exchange Dornsife)

Among those living in food insecure households, 8.3% were Older Adults (LA DPH, 2018)

*Although older adults are often defined as 65+ years, older adults from 60+ years are disproportionately vulnerable

1 in 6 foster youth reported going hungry in the last 12 months

Cal State Fullerton: 31% of all students were FI during the beginning of the pandemic with higher rates of about 40% among Black students, first-generation students, and students with young children (Nobari et al. 2021).

UCLA: 27% of undergraduate students were food insecure in 2020. (UCUES data, UCLA)

Kimberlé Crenshaw, the Columbia law professor who coined the term intersectionality, describes it as:

Many people encompass more than one of these identities and face multiple levels of systemic racism by simply embodying their whole selves.

- 27.4% of Asian Americans in LA County experienced food insecurity (CHIS 2020)

- 49.2% of Pacific Islanders in CA experienced food insecurity (CHIS 2019-2020)

- Food insecurity varies among AAPI sub-groups. Among AAs, Filipinos, Chinese, and Vietnamese are at higher risk compared to other AAs. Elderly AAs (60+ years) had 1.4 times the odds of food insecurity (vs. 18-39 years). (Nhan and Wang, 2022)

- 40% of LA County Latino households experienced food insecurity in 2020 (USC, 2021)

- In CA, 60.5% of Native Americans experienced food insecurity (CHIS 2019-2020)

- Los Angeles food insecurity regional level data not available for the segment

Unique Barriers to Food & Nutrition Security for Priority Populations:

Stakeholders have identified the following unique barriers to food and nutrition security that are commonly experienced by our priority populations:

There is a bi-directional relationship between physical and mental health challenges and food nutrition security. Lack of adequate health insurance, access to physical and mental health services, along with economic and social challenges add to emotional stressors for families and individuals, which could impact caregiving abilities for themselves and family members.

Lack of affordable and consistent childcare has shown to be a significant factor for pushing a family into poverty, especially for households with multiple children. This is not solely due to the expense of childcare itself, but inconsistent childcare access can lead to lost wages and even termination of employment.

Furthermore, children who have limited or no access to quality childcare and/or early learning programs between the ages of 0-5 often fall behind their peers, both socially and developmentally, as compared to their peers.

When there is distrust in the system, especially when there have been negative interactions, people are less likely to utilize public benefits and/or other safety net programs. This perpetuates a cycle of food insecurity that will not be resolved without trust-building opportunities.

Limited language options and communication strategies that don’t take impaired vision and other barriers to communication into account hinder opportunities for certain vulnerable populations to understand how and where they may access social services.

People that may be dependent financially, emotionally, and or/physically on other individuals have limited options for ameliorating their own food insecurity challenges, especially without opportunities to increase self-agency or access to support services.

People with limited mobility, or other needs to fully access programs and services are often not best served by existing structures and processes and may need adaptations beyond ADA compliance measures.

Poverty, the inability to meet such basic needs as food, housing, clean water, clothing, and healthcare in sufficient ways is the number one indicator of food insecurity. Though there are many unique barriers our priority populations face, poverty is shared across all priority population segments.

People with specific dietary preferences and medical requirements often struggle to find those foods available and affordable under existing safety net programs. Similarly, they are oftentimes unavailable or in limited availability at food banks and pantries.

Social isolation and loneliness can often lead to a lack of motivation and depression, hindering one’s ability to prepare healthy meals, leading to nutrition insecurity. Furthermore, lack of a social safety net may indicate a limited ability to access healthy and sufficient food, in addition to other basic human needs.

The Los Angeles Regional Food Bank has appreciated being a part of the Food Equity Roundtable and having the opportunity to provide input from the charitable food network and the people we serve regarding the Roundtable's strategies and goals. We endorse the final report and look forward to partnering to implement the strategic plan.

Michael Flood

President & CEO, Los Angeles Regional Food Bank

6. Approach

Urban agriculture is an important strategy in increasing equity in food systems.

The Roundtable consists of cross-sector leaders focused on food and social equity across LA County, including public and nonprofit service providers, private sector industry, academia, and labor.

The Roundtable formed seven workgroups focused on defining the needs and opportunities for Roundtable intervention. Each of the recommended strategies are grounded in the collective wisdom of the workgroup and Roundtable members.

The result is a coordinated and cross-sector set of recommendations that are supported by our diverse stakeholders. As a two-year pilot, the first year was dedicated to the development of this plan. Now that the Roundtable has adopted it, year two will begin implementation of the objectives and subsequent strategies.

7. A Recipe for Food Equity

Over 200 leaders in the food security and social welfare ecosystem of Los Angeles County engaged in a year-long process to inform the following objectives. Each objective is a step towards achieving our food equity goals. It is accompanied by discrete strategies that the Roundtable is committed to implementing, with concrete actions that fulfill those strategies. We believe this initial set of recommendations will initiate reform and change. This strategic plan is a living document, which we will revisit and refine as we build a just, equitable, and resilient food system.

Neighborhood corner stores are a vital part of the food access ecosystem.

you

know?

Did you know?

Research shows that nutrition education can teach students to recognize how a healthy diet influences emotional well-being and how emotions may influence eating habits. US students receive less than 8 hours of required nutrition education each school year, 9 far below the 40 to 50 hours that are needed to affect behavior change. Additionally, the percentage of schools providing required instruction on nutrition and dietary behaviors decreased from 84.6% to 74.1% between 2000 and 2014.

Objectives

- Modernize the Food System

- Build a Smart & Connected Food System

- Adopt a Dignity of Service Approach

- Elevate Food as Medicine

- Bolster Nutrition Education & Support Healthy Eating

- Champion a Whole Person, Whole Community Approach

Objective 1: Modernize the Food System

For many, our current food system seems to work. We are able to access sufficient amounts of affordable healthy food of varying varieties with considerable ease. Going to the local grocery is a convenient errand; a family trip to the farmers market, an outing. How the food reaches the grocery store or the vendor’s stand is hardly questioned. In fact for many, disruption in the food system and supply was only first felt at the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic when in March 2020 supermarket aisles were suddenly bare with delivery disruptions and sudden shutdowns all over the world.

But, since well before the COVID crisis, our food has largely been grown, harvested, packaged, and distributed in ways that don’t support societal needs and values.

Geographic Access: It is estimated that 1 in 8 Americans live in what is considered a food desert – a term that describes a geographical area where residents do not have equitable access to healthy and affordable foods. In urban areas, this is measured by the lack of a grocery store within a 1 mile radius. Furthermore, in LA County food deserts are primarily found in low-income communities of color, where Black, Latino, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, and Native American communities are shown to experience up to three times the rates of food insecurity. Limited access to public transportation creates an even further burden on individuals and families’ ability to access healthy, affordable food. As noted, this is especially so in LA County, at over 4.7 thousand square miles and a population of over 10 million people (the most populous county in the nation), LA County’s size and breadth creates even greater hurdles to ensuring its 88 individual cities have equitable access to affordable healthy foods.

Climate change and environmental conditions: Climate change is already impacting agriculture- contributing to shortages and price spikes. We can mitigate future climate threats and make our food supply more stable and resilient by reducing food waste, supporting farmers who use regenerative agricultural methods, and facilitating a shift toward less resource-intensive foods.

Diversity and resilience within the food supply chain: Research shows that a trend of corporate concentration in the food industry has made food more expensive and more susceptible to supply chain disruptions, contributing to shortages and inflation. At the same time, governmental policy and corporate practices have excluded people of color from business opportunities; in 1920, 14% of all farmers across the Country were Black but one hundred years later, that proportion has decreased tenfold to 1.4%. We can guard against these trends by taking action to support producers of color and bolster the local and regional food economies, benefitting producers as well as LA County residents.

Click on each strategy to learn more

Action 1: Strengthen secondary markets for farmers of color by linking local and regional producers to public nutrition programs, and collaborate with local businesses and farmers to pilot and test the pop-up store/ mobile models

|

Action 2: Facilitate access to land and other key resources for local food production, including by supporting community gardens in food deserts and hard-to-reach communities

|

Action 3: Support community leaders and entrepreneurs who are exploring innovative and nontraditional farming practices (e.g. hydroponic, vertical gardening, rooftop gardening, bio-intensive gardening, aquaculture, etc.)

|

Action 1: Improve food waste management by testing the viability of food hubs (similar to retail distribution centers) and establish a hub and spoke logistics model to address gaps/limitations in transportation and storage space for recovered/surplus food for smaller non-profit entities.

|

Action 2: Strengthen the capacity food recovery networks to aggregate, store, and transport recovered/surplus food to food pantries and other emergency feeding operations

|

Action 1: Pilot subsidized grocery home delivery methods by partnering with programs such as LA Metro Micro and/or app-based grocery delivery services.

|

Action 2: Test innovative initiatives from public and private sector organizations to bridge the mobility gaps with programs such as:

|

Action 1: Provide small business development opportunities, and capacity building services in operations, marketing, finance management while providing low-interest loans and grant dollars to open local stores in food deserts |

Action 2: Explore the public market model to enable small farmers, retailers, and target audience segments to buy and sell produce at a reasonable price point, as through the farmers’ market model while expanding technical assistance for small food and farm businesses.

|

Action 3: Invest in infrastructure to build the capacity of hyperlocal community-based food assistance nonprofits, such as refrigerated trucks, cold storage, and community convening spaces for food distribution and consumption |

Action 4: Streamline the process of opening new farmers markets

|

Action 1: Support initiatives that aggregate food from small- to mid-size and disadvantaged farmers for redistribution to local consumers, such as through neighborhood markets and innovative food retail models, including public or cooperatively owned markets.

|

Action 2: Adopt the Good Food Purchasing Policy for County operations

|

Action 3: Promote plant-based menu options through nutrition and food procurement policies in food service settings

|

Objective 2: Build a Smart & Connected Food System

Whether it’s harvesting, processing, distribution, consumption, or recovery, our food system is complex. Extracting data from each sector in an efficient and comprehensive way is critical to understanding how to most effectively deliver fresh, sufficient, healthy food to everyone. However, industries are often siloed, and information is not captured in real-time. Data and information that is captured often lacks transparency and granularity and there is no organized effort to integrate across sectors. This hinders our ability to understand the key components of the food system and how, through that lens, it operates as a whole.

Efficiency in the Supply Chain: Lack of integrated data leads to inefficiencies in the food system: for example, mismatches between supply, distribution, demand, and where food is available means food may not always be accessible to those who need it.

Connecting Supply and Demand: There is limited robust data and information developed to understand segments of the LA County population, and regions within the County, that are the most vulnerable to food and nutrition insecurity and issues of food access. Aggregating data can often obscure variability in the populations, the differences in needs of key groups or assets, and the information about vulnerable groups causing them to be overlooked.

Using data to help better understand the food system as a whole will allow for better evaluation of how current practices and interventions impact residents’ ability to consume healthy, sustainable foods.

Click on each strategy to learn more

Action 1: Collect quantitative and qualitative data on the regional supply chain for healthy, sustainable food to improve transparency and strengthen coordination among regional producers, processors, distributors, and retailers.

|

Action 2: Drive efficiency in the food supply chain by using data and technology to reduce food waste and support food recovery by collecting and integrating disparate data sources and building data sharing practices across sources.

|

Action 3: Provide community-based organizations with needed smart and connected tools to support their efforts in increasing food access through safety net program enrollment and food assistance while exploring options for data sharing and coordination between related safety net programs.

|

Action 4: Develop a "food systems map" of assets and key features in the LA County food system.

|

Action 1: Develop guidelines for identifying and addressing bias in data collection. Bias in data can come in the form of reporting bias - when available information is underreported, and selection bias- when certain people/groups/organizations are not represented in data which can lead to poorly collected datasets and community representation.

|

Action 2: Find resources and develop methods for evaluating food insecurity among people with dietary restrictions.

|

Action 1: Collect and integrate disparate data sources (e.g. from urban farmers and food generators to food recovery data) to centralize information, map the landscape, and standardize data sharing and integrate data sources for food recovery units to understand where the need is.

|

Action 2: Build collaboration and data sharing between cross sector partners such as public and private sector food service organizations to drive efficiencies in the supply chain- enabling reduction in food waste and supporting food recovery efforts.

|

Action 1: Expand initiatives to integrate online benefits applications for food, cash assistance, healthcare, childcare, and other basic needs to reduce the complexity and time it takes to apply for multiple benefits programs. |

Action 2: Promote nutrition directories where individuals accessing public benefits are supported in the enrollment process, including where and how to acquire culturally diverse food options. |

Action 3: Partner with programs that serve our priority populations to ensure that they are delivered information in an appropriate and accessible way (i.e., digital applications).

|

Objective 3: Adopt a Dignity of Service Approach

Our food system as it currently operates fails to provide access to affordable, sufficient, culturally relevant foods to all residents. The stigma and shame associated with benefits enrollment coupled with a system that doesn’t center the individual has led to a broken approach.

In a truly equitable system, dignity is not only shown to the client but is a dual relationship between client and processor. Why is this important? Because it elevates the interaction from transactional and hierarchical to one that is equal and purposeful on both sides.

The Unique Needs of Those We Serve: The current food system needs to revisit its design to be more inclusive of diverse races, cultures, languages, and genders. The food system needs to adopt a strong customer-centric approach that better understands the unique barriers faced by our priority population segments and provides dignified support and services. Dignity is more than an approach, it’s a value- one that needs to be ever present in our food system.

Click on each strategy to learn more

Action 1: Invest to improve the quality of customer service by making offices and call centers more accessible, increasing co-location of County department offices in more accessible spaces like schools/colleges, health clinics, food banks, and community centers targeted in high-need neighborhoods.

|

Action 2: Train public benefit providers on implicit bias and empathy & sensitivity.

|

Action 3: Redesign grocery and meals sites to promote a sense of inclusion and foster community camaraderie and ensure sites and safety net program offices are open at hours that meet the needs of the priority populations they serve.

|

Action 4: Explore opportunities to redesign marketing materials to be more approachable and welcoming.

|

Action 5: Support the creation of community eating spaces for individuals prone to social isolation

|

Action 1: Cross promote programs and streamline enrollment processes to ensure clients are maximizing their benefits and receiving all the support they are eligible for.

|

Action 2: Train safety net providers with information regarding eligibility criteria across public benefit programs to advance coordinated, dual-enrollment processes.

|

Action 3: Expand number of id/name change clinics and more medical-legal partnership programs which is a unique barrier for transgender and gender nonconforming community

|

Action 4: Increase collaboration with transitional-age-youth shelters and homeless service providers to ensure enrollment assistance for unhoused youth upon entering the homeless services system

|

Action 1: Support more telephonic and/or face-to-face enrollment processes for those uncomfortable or unfamiliar with technological interventions and support the development of promotional materials and plans that are accessible to people with varied disabilities.

|

Action 2: Develop youth-oriented marketing materials to promote public benefits to college students and reduce stigma associated with their use.

|

Action 3: Develop targeted messaging campaigns that include in-language messaging and trusted messengers to deliver information about CalFresh and how it does not affect public charge determinations.

|

Action 4: Identify CBOs that facilitate enrollment to safety net programs, and partner on cross-promotional strategies including mobile enrollment programs that travel to encampment sites and partner with temporary shelters and permanent supportive housing providers

|

Objective 4: Elevate Food as Medicine

We know that the relationships we build, the places we find joy, and the purpose in our work all have a direct connection to our overall physical and mental well-being. And yet the food we eat, a representation of our culture, our connection to the earth, and a cornerstone of gathering, is often overlooked as an opportunity to generate wellness. The health of a person is not simply defined as a lack of disease; rather, it is defined by a person’s ability to thrive socially, mentally, and physically. Indigenous cultures teach us, these traditional Native American food practices promote the values of eating together, eating locally and seasonally, and being conscious of where and how it’s grown.

Nutrition & Health In Adults : Nutrition is a critical component of health and wellness, both with regards to preventative and palliative care. In fact, poor nutrition and dietary habits have been linked to higher risks of cancer, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and even premature death. And yet, according to the LA County Department of Public Health, the percentage of adults in the County that eat five or more servings of fruits and vegetables each day is only 14.6% with lower-income areas falling as low as 10.7%- trailing behind the national average of 23.2% by more than half.

Nutrition and Childhood Development: Nutrition is especially important in children. Children that are food insecure not only have poorer health and development outcomes, they don’t perform as well in school, with higher rates of absenteeism and tardiness, along with aggression and other undesirable psychosocial outcomes. Insufficient nutrition may actually lead to cognitive impairment among children.

Although access and affordability of healthy, nutrient dense foods is not available to all, it is still considered a more cost-effective way of managing overall health and wellness when compared to the costs associated with more formal medical care. By recontextualizing healthy food as a wellness strategy, and taking its true cost into account, a whole new perspective and urgency around prioritizing healthy nutrient dense food is created.

Click on each strategy to learn more

Action 1: Develop a cohesive medical professional training methodology to support intervention strategies for food and nutrition insecurity in patients, especially for those who treat and diagnose allergies/intolerances.

|

Action 2: Expand nutrition incentives that encourage people to consume fresh vegetables and fruits.

|

Action 3: Support collaboration between physical and mental health service agencies to ensure effective outreach and enrollment strategies across MediCal and food services programs.

|

Action 4: Engage health plans to explore the feasibility of providing medically supported food and nutrition interventions to MediCal recipients, enabling doctors to prescribe food as medicine. |

Action 1: Work in collaboration with health plans to effectively implement the CalAIM proposal to offer medically tailored meals to meet the unique dietary needs of those with chronic diseases. Train medical professionals and staff on how to instruct patients to enroll in reimbursement opportunities through CalAIM

|

Action 2: Move publicly-funded food programs that offer nutritional counseling to ensure that staff providing such counseling are knowledgeable of dietary restriction needs and have the appropriate resources available to patients, including referrals for medical nutritional therapy and guidance on food substitutions.

|

Action 3: Ensure that emergency food distribution programs have diverse food options in order to fulfill the food needs of people with dietary restrictions, and strengthen staff and volunteer knowledge and capacity to distribute specialized food options, as needed.

|

Objective 5: Bolster Nutrition Education & Support Healthy Eating

We know that the best chance for a behavior to be exhibited as an adult is to learn it as a child. And yet, we don’t model and teach where our food comes from, what food can do for our body, mind, and soul, or how to prepare it in a way that feeds and nourishes us. Moreover, many people who know how to eat healthfully nonetheless find it difficult to practice healthy eating habits on a regular basis. Unhealthy options are often more convenient and/or affordable — for example, soda is an easy choice for people who lack access to drinkable tap water and can’t stretch their food budget enough to buy expensive bottled water.

Eating Healthy in Childhood: There are multiple influences on how a child learns life-long eating habits. The two most prevalent are, of course, the home and school. Parents prepare the majority of meals but they pass on family recipes, celebrate cultural traditions, and create spaces to gather. Similarly, childcare facilities and schools are the other main influence on a child’s diet. Local education agencies can play a critical role in improving both health/nutrition education and health/food literacy to support positive health outcomes. Ensuring equitable access to comprehensive, culturally-appropriate, and skills-based health and nutrition education in schools is important to promote lifelong healthy eating behaviors.

Eating Healthy in Adulthood: Comparably, many adults struggle to incorporate healthy meals on a regular basis. Availability and access to food that meets dietary needs can often be cost prohibitive, difficult to find, and an emotional stressor. Nutrition education is critical to improving food literacy, cooking, and shopping confidence. Furthermore, by making healthy food more convenient and creating environments that support healthy eating habits, we can drive higher consumption of healthy food.

Eating Healthy as a Community: Our community, those with whom we gather, significantly influences our eating habits. When knowledge of how to cook and eat nutritiously is shared, it leads to better eating and health outcomes for all. By increasing that knowledge through public campaigns, cooking workshops, and other engagement strategies to increase food literacy, consumption of healthy food increases.

Nutrition education has proven to be critical in not only instilling lifelong healthy eating habits, but promoting behavioral change opportunities, like mindful eating, to support health and wellness.

Click on each strategy to learn more

Action 1: Update messaging and definitions of nutrition and nutritious meals to include cultural preferences and dietary needs and promote consistency across all LA County communications.

|

Action 2: Launch baseline measurements of nutrition security for LA County across the priority populations and implement measures to track changes in food and nutrition security.

|

Action 3: Establish accountability for consistent and scientifically backed messaging regarding nutritious food options among all consumer information touchpoints e.g. dietitians, doctors, health clinics, teachers/educators, media etc. have consistent understanding and messaging around what is nutritious food intake and healthy diet.

|

Action 4: Ensure meals and snacks being served at before and after school care programs meet nutritional needs and serve children with dietary restrictions and explore the integration of nutrition education programs as part of the curriculum for after-care programs.

|

Action 1: Leveraging communications channels that engage local community leaders & trusted messengers, faith based organizations, cultural centers, ethnic media, digital/video campaigns for youth, and grassroots community based organizations.

|

Action 2: Create opportunities for families and individuals to attend public teaching kitchens, cooking workshops, and grocery store based nutrition education programs in hard-to-reach communities with nutrition information and recipes that match cultural and geographical needs.

|

Action 3: Coach restaurants on the importance of safe handling of food for those with allergies and dietary restrictions, including food handling processes

|

Action 4: support the expansion of community-led or participatory nutrition education programming

|

Action 1: Collaborate with the local colleges (i.e. California Community Colleges) to create a universal campaign to promote food and nutrition security and wellness for college campuses that integrates trauma-informed services, addresses social stigmas, and emphasizes holistic health and wellness.

|

Action 2: Partner with colleges to increase the visibility and utility of centralized platforms for students in need of food assistance.

|

Action 3: Ensure that college CalFresh outreach efforts are engaged with support programs working with foster youth, parenting students, youth who have been involved in the justice system, and other disproportionately impacted populations as well as community education programs, dual enrollment programs, and K-12 Homeless liaisons.

|

talking about schools?

School nutrition programs across the state are currently undergoing major changes: as of the 2022-23 school year, the California Universal Meals policy mandates that all public and charter schools must offer breakfast and lunch to any student at no charge. Schools are working hard to implement the policy, and the California Department of Education is monitoring their efforts. Based on consultation with school nutrition leaders, the Food Equity Roundtable will refrain from making any recommendations or commitments related to school nutrition while schools are still adjusting to this change.

Objective 6: Champion a Whole Person, Whole Community Approach

Hunger is not simply a matter of access or affordability. Rather, there are many factors that ultimately lead to food insecurity. In order to truly ameliorate food insecurity and achieve food equity, a person must be treated as a whole person with varying needs, challenges, strengths, and opportunities. The recommended strategies will be complemented by a trauma-informed approach, as adopted by the State of California, which screens individuals for childhood trauma that affect them throughout their lives. Though these strategies may not be directly related to achieving food and nutrition security, our Roundtable of social justice leaders represent organizations that have significant expertise in addressing these issues which allow for influence and impact on critical issues that ultimately support our food and nutrition security agenda.

- Economic Stability: The ability to afford basic needs like safe, healthy food, housing, and healthcare significantly impacts well-being and quality of life, potentially leading to physical and emotional distress.

- Education Access & Quality: One’s ability to have a quality education leads to exponentially better outcomes, including longer, healthier lives. Quality primary education leads to greater opportunities later in life with the ability to go to college, leading to greater workplace opportunities.

- Health Care & Quality: The connection between a person’s ability to access affordable healthcare and their ability to understand and manage their own health and wellness.

- Neighborhood & Built Environment: How the environment within which a person lives, works, and plays has an impact on their overall well-being and ability to succeed.

- Social & Community Context: A feeling of community, healthy bonds and relationships, and core family unit all lead to healthier minds, bodies, and souls.

Click on each strategy to learn more

Action 1: Extend the hours and capacity of existing after-school care programs and expand programs to middle and high schools in hard-to-reach communities.

|

Action 2: Ensure meals and snacks being served at before and after school care programs meet nutritional needs, serve children with dietary restrictions, and explore the integration of nutrition education programs as part of the curriculum for after-care programs.

|

Action 3: Landscape the current availability of quality affordable day care centers in hard-to-reach communities and explore opportunities for expansion, such as subsidies, workforce training, etc.

|

Action 1: Collaborate with LA County’s Poverty Alleviation and Anti-Racism, Diversity, and Inclusion initiatives to address economic challenges and racial bias within communities of color and improve hiring and retention outcomes.

|

Action 2: Work in close collaboration with public and private entities to ensure effective outreach of health and dental clinics within under-resourced communities

|

Action 3: Include food security assessment in the Coordinated Entry System to ensure a timely connection to food resources, including access to mobile phones to facilitate completion of the GetCalFresh application, access to the YourBenefitsNow mobile app, WIN app, and similar app-based resources.

|

Action 1: Support job growth in the food supply chain with a focus on local hire.

|

Action 2: Enable employers to offer adequate benefits and training for professional upward mobility.

|

8. Policy Change for

Systems Transformation

Policy change at the federal, state, and local level will be crucial for achieving food equity. By unifying our voices in support of food systems transformation and partnering with other coalitions on shared goals, we can make policy work better for the people of LA County.

The Roundtable will monitor legislation and budget policy to identify opportunities for advancing our priorities. When relevant, we may also provide input on rulemaking and program administration; in some cases, this is the most effective way to advance food equity. We will work to ensure that our goals are reflected within the County’s own policies, and we can facilitate hyperlocal policy change by engaging with the 88 cities across Los Angeles County.

Three budget priorities we can champion at all levels of government include:

- Nutrition incentive programs such as Market Match

- Distribution of free, healthy prepared meals to vulnerable/low-income populations with barriers to storing or preparing food

- Community-led and innovative agricultural initiatives

The below sections outline key areas of policy authority at each level of government and upcoming opportunities to advance Roundtable priorities.

Learning about nutrition in schools is one of the best ways to instill life-long good eating habits.

- Federal Policy

- State Policy

- Local Policy

- Long-Term Policy Goals

Federal Policy

All of our most powerful public benefit and food safety net programs are funded and regulated by federal policy. These programs lift millions of people out of poverty each year, addressing the number one driver of food insecurity. Advocacy is critical to ensure the programs meet local needs.

Several federal departments have important roles in food and nutrition security. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) oversees the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, known locally as Calfresh) and several other food safety net programs. Federal healthcare policy, overseen by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) determines which types of health and wellness services – including nutrition counseling and food assistance – are eligible for federal reimbursement.

Simultaneously, the USDA is responsible for the nation’s agricultural policy. Agricultural policy has historically incentivized high crop yields without much consideration for the food’s nutritional properties or the land’s ability to sustain high yields into the future. The resulting abundance of low-quality food has not prevented food insecurity, nor has it supported overall wellbeing. However, thought leaders and advocates are building consensus to align agricultural policy with the nation’s public health and environmental goals.

Short-Term Opportunities to Advance Federal Policy Priorities

The Federal legislature is currently considering proposals in multiple areas of interest:

The Farm Bill determines funding and policies for the nation’s largest food assistance program – the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), known locally as CalFresh – alongside a range of other food and farming programs. Renewed approximately every 5 years, it is up for reauthorization in 2023, providing the opportunity for immediate advocacy efforts by the Roundtable and partners. Some critical policy goals for the upcoming reauthorization include:

- Maximize the impact of SNAP (CalFresh), especially for priority populations

- Expand initiatives that promote health and nutrition

- Create a more sustainable and resilient food supply

ABOUT THE FARM BILL

The Farm Bill

The Farm Bill is the nation’s most comprehensive set of policies governing both food and agriculture. Congress enacted the first version of the Bill during the Great Depression to address a seeming paradox: simultaneous food surplus and widespread hunger. Its earliest provisions were designed to prevent crop overproduction and reduce soil erosion, which had contributed to the Dust Bowl environmental disaster, setting precedence for enacting sustainable and resilient agricultural practices today.

More recent versions of the Farm Bill have also contained nutrition assistance programs. The 2018 Farm Bill mandated more than $400 billion in spending over five years for nutritions assistance, with 80% of that going toward SNAP. The 2023 Farm Bill is a paramount opportunity to improve SNAP and other programs for the immediate benefit of under-resourced individuals and families. Simultaneously, we can support policies that will help prevent future agricultural disasters and potential disruptions to the food supply. Priorities include:

- Improve SNAP

- Reduce eligibility restrictions for immigrants, college students, and justice-involved individuals

- Reduce barriers to enrollment by permanently preserving the administrative flexibilities allowed during the public health emergency

- Make SNAP more useful for people who face barriers to preparing their own meals – including unhoused individuals, older adults, people with disabilities, and single parents – by allowing all participants to use SNAP dollars for prepared foods

- Base SNAP benefit allotments on the more adequate Low-Cost Food Plan

- Reduce eligibility restrictions for immigrants, college students, and justice-involved individuals

- Expand initiatives that promote health and nutrition

- The Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program (GusNIP), which makes healthy food more affordable for program participants

- Healthy Food Financing, which supports the sale of healthy food in under-resourced neighborhoods

- Urban agriculture, food recovery, and innovative community-led food initiatives

- Upgrades to water infrastructure, particularly in low-income communities

- The Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program (GusNIP), which makes healthy food more affordable for program participants

- Change agricultural policy in support of a more sustainable and resilient food supply

- Promote healthy soil, manage the water supply, and mitigate climate change by incentivizing regenerative practices (such as cover cropping) and disincentivizing or regulating pollutive practices (such as heavy use of synthetic inputs)

- Bolster local and regional markets and support participation by small and minority farmers

- Increase funding for over-subscribed conservation programs such as EQIP, and restrict eligibility to operations that actively benefit the environment and nearby communities, rather than simply minimize harm.

- Promote healthy soil, manage the water supply, and mitigate climate change by incentivizing regenerative practices (such as cover cropping) and disincentivizing or regulating pollutive practices (such as heavy use of synthetic inputs)

Child Nutrition Programs such as school meals and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) can be updated every five years through Child Nutrition Reauthorization. These programs directly improve child health, and Congress is currently considering Reauthorization bills such as The Wise Investment in our Children Act. Reauthorization would enable key changes to make child nutrition programs more accessible to mothers and children, such as:

- Extending WIC eligibility for children up to age six

- Extending WIC certification periods for infants for two years instead of one

- Extending WIC eligibility for breastfeeding and postpartum mothers to two years

The Food Labeling Modernization Act would promote healthy choices by requiring food packaging to more clearly convey the nutritional quality of the package’s contents, and would help consumers manage diet-related diseases through warning symbols for unhealthy ingredients and new disclosures for key allergens.

State Policy

California often takes leadership in areas where federal policy falls short — filling gaps in the food safety net, and making strides toward a climate-resilient agricultural economy.

Though a large agricultural producer, much of what California grows is in the form of specialty products (e.g., almonds) designed for national supply chains. The result is that much of this food is exported out of the state, leaving even local consumers largely reliant on food that is then imported back into the state. But, there are policies and programs the state can implement to support the small- to midsize farms that do provide food to local consumers. For example, the State can provide funding and technical assistance in support of small and/or farmers of color looking to receive certification for sustainable agricultural practices.

State agencies have the ability to bolster the federal efforts to increase the consumption of nutritious foods as part of an effective health and wellness strategy, and a state can also implement its own efforts aimed at increasing nutrition security. This may include leveraging federal healthcare dollars to purchase or subsidize safe, healthy foods for priority populations, specifically those with higher health risks and or dietary restrictions. California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAim), for example, provides medically tailored meals to individuals following a recent hospital stay as part of a comprehensive recovery strategy.

Furthermore, in addition to implementing federal safety net programs, California can and has augmented those programs to ensure priority populations truly benefit. The California Food Assistance Program (CFAP) is a state-run SNAP-type program that provides benefits to those ineligible under federal guidelines, such as qualified non-citizens. Advocacy at the state level has this ability to leverage and build upon these existing efforts to truly support the food insecure in a targeted and effective way.

Short-Term Opportunities to Advance State Policy Priorities

The State legislature is expected to consider proposals covering the following priorities in the upcoming legislative session:

- Expand CFAP to income-eligible people, regardless of immigration or citizenship status, of all ages

- Make assistance available for small and/or farmers of color to adopt or receive certification for sustainable, climate-resilient agricultural practices

Local Policy

Local government has the most agency with regards to targeted and tailored impact. It has the ability to provide support for federal and state programs that are oversubscribed and has the most influence and authority regarding local land use, taxes, procurement, and economic development decisions, all of which play key roles in affecting food and nutrition security.

Economic and land use policies have, historically, played a key role in creating food deserts and exacerbating food insecurity at a systemic level. It’s key to ensure these unjust and inequitable policies are not only dissolved but reversed to now heal the damage they have caused. Efforts like Good Food Zones and Urban Agriculture Incentive Zones acknowledge historic divestment in neighborhoods and communities of color while implementing place-based strategies for increasing access and affordability of safe, healthy foods in culturally appropriate ways. By instituting Good Food Purchasing Policies, local municipalities recognize the great influence their own purchasing power has in creating transparent and equitable food systems that support local economies, health, valued workforce, animal welfare, and environmental sustainability.

Local Policy Priorities

Local County and City governments can consider near-term policy changes to support Roundtable goals such as:

- Increase access to healthy and/or locally-produced food in low-income communities by establishing or strengthening economic development and land use policies such as Good Food Zones and the Urban Agriculture Incentive Zones

- Expand adoption of the Good Food Purchasing Policy and related procurement goals by institutions across the county to increase access to healthy and climate-friendly food items

Long-Term Policy Goals

The Roundtable will periodically re-evaluate the policy landscape and identify opportunities to support the following types of policy changes aligned with our long-term goals.

- Goal 1:

- Goal 2:

- Goal 3:

- Goal 4:

Goal 1: Support the ability to afford healthy food by advancing policies that:

Expand the Impact of Food Safety Net Programs

- Expand the types of allowable food purchases in food assistance programs (e.g. WIC or SNAP Restaurant Meal Program, hot food at grocery stores) to include a greater variety of healthy options, including for people with dietary restrictions, such as gluten-free and other medical conditions.

- Eliminate or minimize eligibility and verification requirements for food benefit programs other than income (e.g., asset limits, time limits, interview requirements, work requirements, proof of immigration status) and lift restrictions such as those facing justice-involved individuals.

For example:- Support federal policy changes to make foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 categorically eligible for SNAP/CalFresh to mirror Medicaid policy and/or support state-funded nutrition benefits for foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 who are otherwise ineligible for CalFresh.

- Support federal policy changes to make foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 categorically eligible for SNAP/CalFresh to mirror Medicaid policy and/or support state-funded nutrition benefits for foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 who are otherwise ineligible for CalFresh.

- Increase benefit levels in food assistance programs to address the complete needs of food-insecure populations.

- Extend eligibility for food assistance programs to additional populations who would benefit.

Expand the Impact of Public Benefit and Financial Assistance Programs that Offset Food Costs

- Support the streamlining and/or integration of participant application/certification processes across multiple safety net programs.

- Expand SSI eligibility by eliminating the asset test.

- Support efforts to increase access to affordable housing and rental assistance.

- Increase access to tax credits among low-income individuals.

- Expand Guaranteed Income pilot programs.

Goal 2: Improve access to healthy food by advancing policies that:

Make healthy, affordable, and climate-friendly food more readily available through retail

- Strengthen the supply chain from Los Angeles regional growers to local farmers markets and healthy food stores in low income communities of color.

- Support the establishment or expansion of healthy food retail in low-income communities of color.

- Improve and expand healthy food recovery from food businesses.

- Increase access to online and delivery services from grocery stores, farmers markets and other outlets.

- Expand the types of allowable food purchases in food assistance programs (e.g. WIC or SNAP Restaurant Meal Program, hot food at grocery stores) to include a greater variety of healthy options, including for people with dietary restrictions, such as gluten-free and other medical conditions.

- Eliminate or minimize eligibility and verification requirements for food benefit programs other than income (e.g., asset limits, time limits, interview requirements, work requirements, proof of immigration status) and lift restrictions such as those facing justice-involved individuals.

For example:- Support federal policy changes to make foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 categorically eligible for SNAP/CalFresh to mirror Medicaid policy and/or support state-funded nutrition benefits for foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 who are otherwise ineligible for CalFresh.

- Support federal policy changes to make foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 categorically eligible for SNAP/CalFresh to mirror Medicaid policy and/or support state-funded nutrition benefits for foster youth and justice-involved youth between ages 18-26 who are otherwise ineligible for CalFresh.

- Increase benefit levels in food assistance programs to address the complete needs of food-insecure populations.

- Extend eligibility for food assistance programs to additional populations who would benefit.

Support food sovereignty by enabling communities to independently grow their own food

- Support community gardening and urban agriculture initiatives in low-income communities such as by increasing access to resources like compost, water, and technical assistance.

- Secure and protect land for food production.

Expand capacity of the private and nonprofit sectors to deliver food assistance and/or partner with public food assistance programs

- Increase capacity of free food distribution programs to store and distribute healthy food.

- Promote healthcare initiatives that improve access to healthy food, such as produce prescription programs and medically tailored meals.

- Improve school capacity and infrastructure for preparing healthy meals and offering options for students with dietary restrictions.

- Increase access to safe, healthy food among college students, especially those who are transitioning from the foster care or juvenile justice systems, such as through financial aid allocations or voucher programs.

- Support proposals to expand eligibility for congregate meal programs to dependent adults ages 18-60 with disabilities.

Goal 3: Promote consumption of healthy food by advancing policies that:

Support consumers in making healthy choices

- Create or expand nutrition incentive programs/financial supports for safe, healthy food.

- Increase healthcare coverage of nutrition counseling and transportation to food services.

- Update food and nutritional supplement labeling requirements to cover additional allergens such as gluten-containing grains, to standardize definition of “sell by” dates, and/or to regulate use of terminology such as “natural” and “climate-friendly.”

- Disincentivize consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages such as through policies that address production, pricing, or marketing.

- Support availability and affordability of clean drinking water, such as through CalFresh/EBT water supplements and improvements to our water supply and infrastructure.

Support public agencies, businesses, and nonprofits in offering healthy options

- Improve utilization/appeal of farmers markets.

- Increase availability of free EBT machines, for both WIC and CalFresh, for farmers, mobile markets and other non-traditional healthy retail outlets.

- Incentivize or partner with food producers or retailers to sell more healthy and fewer unhealthy products.

- Increase funding to distribute free, healthy prepared meals to vulnerable/low-income populations with barriers to storing or preparing food.

- Expand adoption of the Good Food Purchasing Policy by institutions across the County.

Goal 4: Improve the long-term resilience and sustainability of the food system by advancing policies that:

Ensure the food supply entering LA County from other areas is sustainable and reliable

- Support state and federal efforts to advance environmentally responsible and climate-resilient agricultural methods.

- Strengthen environmental regulations for food production.

- Support anti-trust regulation to prevent price fixing and exploitation of food system workers.

- Expand infrastructure and technical assistance for small food and farm businesses.

Improve consumer access to a wide variety of sustainable and local food options

- Support access to land for agriculture and food business ownership by minority communities.

- Mitigate climate impacts of agricultural production by procuring climate-friendly healthy foods.

- Support access to unused government spaces and resources for the production and distribution of affordable healthy food.

- Increase public funding for community-led and innovative agricultural initiatives, such as those that convert unused spaces into food producing areas (including non-traditional farming i.e. vertical gardening, rooftop gardening, biointensive) and strengthen local distribution networks.

9. What's Next?

After a year-long review and multiple convenings, Los Angeles County stakeholders believe there is a strong need for a coordinated, comprehensive, and cross-sector approach to address systemic barriers in the current food system. There is a need for a centralized approach to dealing with this crisis in our region (not just when a global emergency strikes like it did in March of 2020 with the global COVID-19 Pandemic) and coordination that addresses food insecurity each and everyday

First and foremost we are committed to developing a more modern, inclusive, and just food system. We will leverage momentum — recently formalized with the National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health — to build a healthier, stronger and nourished Los Angeles County.

This plan is a collective vision of the LA County Food Equity Roundtable for achieving food equity in LA County. Together, and going forward we will now begin to expand upon innovative work, pilot new projects, gather data, and share findings to achieve replicability and scalability for LA County and beyond.

The LA County Food Equity Roundtable will continue to strengthen collaborations to implement the recommended actions in the strategic plan, adopt a phased approach to implement the priority actions, and conduct an annual review of the strategic plan to ensure its effectiveness in achieving the North Star goal.

We understand that this strategic plan is in no way a comprehensive and exhaustive set of solutions to address the inequities within the current food system. However, the LA County Food Equity Roundtable believes that this initial set of recommendations will catalyze reform that will help lead to an equitable, sustainable, and resilient food system for all.

It was inspiring to participate in the Food Equity Roundtable and sub-committees and be surrounded by people across LA County committed to ending hunger and food insecurity from many different vantage points. By the end of the first phase, it was clear we have the collective ideas, deep desire, and resources to solve this problem. Now on to implementation!

Lena Silver

Associate Director of Litigation and Policy Advocacy, Neighborhood Legal Services of Los Angeles County

Acknowledgements

LA County Food Equity Roundtable Chairs

Cinny Kennard, Executive Director, Annenberg Foundation

Alison Frazzini, Policy Advisor, Los Angeles County Chief Sustainability Office

Roundtable Members

Jackie Contreras, Interim Director, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Paula Daniels, Founding Chair, Center for Good Food Purchasing

La Shonda Diggs, Division Chief, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Efrain Escobedo, Vice President of Public Policy and Civic Engagement, California Community Foundation

Jamie Fanous, Senior Policy Advocate and Organizer, Community Alliance with Family Farmers

Charity Faye, Program Manager of Sisters in Motion, Black Women for Wellness

Kathy Finn, President, United Food & Commercial Workers 770

Michael Flood, President & CEO, Los Angeles Regional Food Bank

John Kim, CEO, Catalyst California

Tony Kuo, Director, Division of Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention,

Los Angeles County Department of Public Health

Ambassador Michael Lawson, President & CEO, Los Angeles Urban League

Abigail R. Marquez, General Manager, City of Los Angeles, Department for Community Investment For Families

Rick Nahmias, Founder & CEO, Food Forward

Vy T. Nguyen, Senior Director, Special Projects and Communications, Weingart Foundation

Janette Robinson Flint, Executive Director, Black Women for Wellness

Kiran Saluja, Executive Director, PHFE Women, Infants, & Children (WIC)

Maryam Shayegh, Nutrition and Wellness Coordinator, Los Angeles County Office of Education

Lena Silver, Associate Director of Litigation and Policy Advocacy, Neighborhood Legal Services of Los Angeles County

Frank Tamborello, Executive Director, Hunger Action Los Angeles

Christine Tran, Executive Director, Los Angeles Food Policy Council

John Wagner, Executive Vice President, First 5 Los Angeles

LA Food Equity Roundtable Team

Swati Chandra, Director, LA County Food Equity Roundtable

Natasha Wasim, Program Manager, LA County Food Equity Roundtable

Violeta Jimenez, Assistant Program Manager, LA County Food Equity Roundtable

Anthony Thomas, Student Worker, LA County Food Equity Roundtable

Celina Navarrete, Summer Student Worker, LA County Food Equity Roundtable

Steering Committee

Lisa Cleri Reale, Principal, Lisa Cleri Reale & Associates

Gary Gero, Former Chief Sustainability Officer, Los Angeles County Chief Sustainability Office

Tamara Hunter, Executive Director, Los Angeles County Commission for Children and Families

Rita Kampalath, Acting Chief Sustainability Officer, Los Angeles County Chief Sustainability Office

Dipa Shah-Patel, Director, Nutrition and Physical Activity Program, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health

Lauren Uy, Program Associate, California Community Foundation

Technical and Policy Advisors

Robert Beck, Human Services Administrator, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Jared Call, Senior Advocate, Nourish California

Ana-Alicia Carr, Community Advocacy Director, American Heart Association Los Angeles Division

Sharon Cech, Program Director, Urban & Environmental Policy Institute, Occidental College,

Deisy Chilin, Human Services Administrator, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Julie Ciardullo, Senior Policy Advisor, City of Los Angeles, Office of Sustainability

Kayla de la Haye, Associate Professor, USC Department of Population and Public Health Sciences

Raj Dillon, Sustainability Policy Advisor, Los Angeles County Chief Sustainability Office

Roobina Gerami, Human Services Administrator, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Hugo Giron, CAB Coordinator, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Jeremy Goldberg, Worldwide Public Sector Director of Critical Infrastructure, Microsoft

Abraham Gomez, Administrative Services Manager, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Lisa Hayes, Human Services Administrator, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Matthew King, Communications Consultant, May77 Communications

Veronica McDonnell, Assistant General Manager, City of Los Angeles, Department for Community Investment For Families

Emily Michels, Coordinator of Public Policy and Government Relations, SoCal Grantmakers

Natasha Moise, Program Officer, First Five Los Angeles

Derek Polka, Policy and Research Manager, Los Angeles Regional Food Bank

Nestor Requeno, Human Services Administrator, Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services

Ellah Ronen, Director of Strategy & Impact, DoGoodery

Janet Valenzuela, Senior Policy Associate, Los Angeles Food Policy Council

Valeria Velazquez Dueñas, Senior Manager of Farmers’ Programs, Sustainable Economic Enterprises of Los Angeles

May Wang, Professor, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health

Kelly Warner, Program Manager, Nutrition and Physical Activity Program, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health

Roundtable Working Group Members

Alvaro Aguila, Program Director, Foster and Kinship Care, Los Angeles City College

Suzette Aguirre, Public Health Nutritionist, Nutrition and Physical Activity Program, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health

Tiffani Alvidrez, Western Regional Policy Manager, Instacart

Nina Angelo, Farmers’ Market Manager, Sustainable Economic Enterprises of Los Angeles

Ani Aratounians, Director of Nutrition Services, Los Angeles Regional Food Bank

Eric Ares, Senior Manager, Homeless Systems Change, United Way of Greater Los Angeles

Anna Avdalyan, Assistant Director, Los Angeles County Aging & Disabilities Department

Marianna Babboni, Project Manager, USC Public Exchange

Nadia Bedrosian, Health Educator II Registered Dietitian, LA Care Health Plan

Susan Belgrade, Senior Director, Jewish Family Service Los Angeles

Commissioner Carlos Benavides, President, Los Angeles County Commission on Disabilities

Evelyn Blumenberg, Director, Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs

Robert Boller, Director of Programs, Project Angel Food

Sherry Bonanno, Former Executive Director, Hollywood Food Coalition

Diana Campos-Jimenez, Interim Executive Director, Los Angeles Community Garden Council

Velma Cervantes, Program Coordinator, Southeast Area Social Services Funding Authority, Senior Services

Katherine Chen, Founder, Edible Healing Garden

Consuelo Cid, Project Coordinator, Sustainable Economic Enterprises of Los Angeles